[ad_1]

In the office market, obtaining backing for new office builds and lining up acquisition financing for M&A deals will prove tough in this environment. But refinancing is particularly daunting. However, under the right circumstances, some office owners will be able to pull it off.

Office properties are facing what could plausibly be called a financing drought. Suffering from the same macroeconomic trends that have impacted commercial real estate writ large, including climbing interest rates and a spate of bank failures, the office sector’s access to financing has also been hindered by challenges unique to its sphere.

Foremost amongst these is the post-pandemic uncertainty still plaguing office properties in an era where many employees who once commuted to their offices daily are content to work from home and employers, in turn, are reluctant to lease the same square footage as before. In fact, many quickly learned they can save money by finding smaller accommodations. This has triggered fears of potential defaults on existing loans, with some prominent industry names, including Brookfield Corp. and PIMCO, defaulting on certain properties in the first half of this year.

“Given the current challenges in the office sector, there will likely be a variety of approaches taken to address the issues at hand,” said Darin Mellott, vice president of capital markets research at CBRE. “Financial regulators have encouraged lenders to work with borrowers, so we may see some short-term extensions granted. In other cases, refinancing may be possible, but additional capital will likely need to be injected into the deal.”

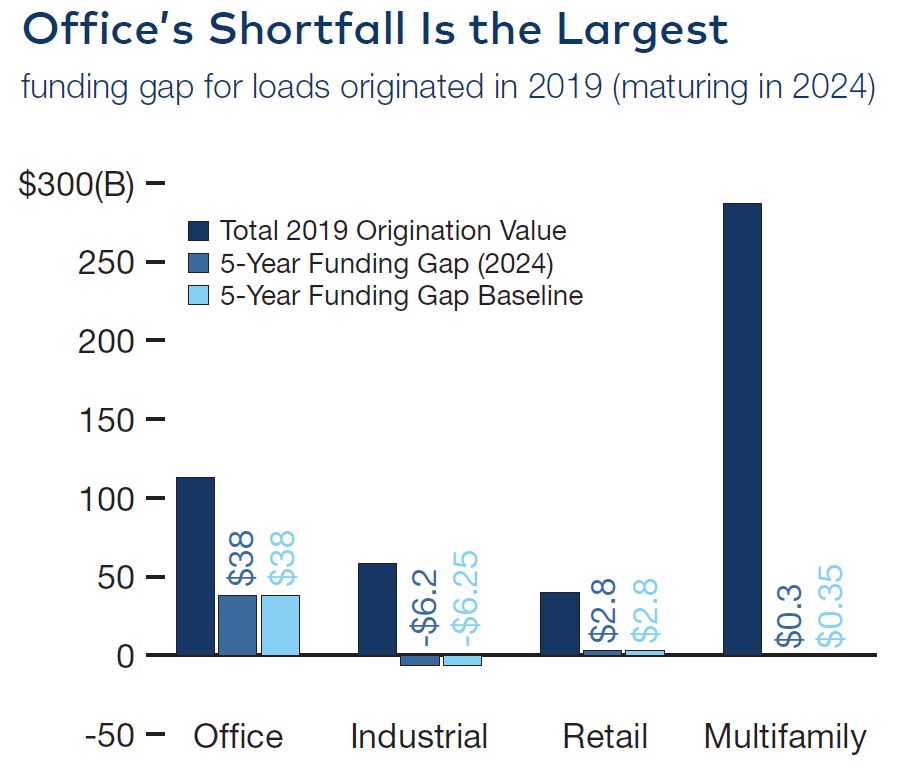

In a report issued earlier this summer, CBRE warned that the office sector’s debt funding gap was likely to increase as investors are forced to refinance at a loan-to-value ratio lower than that of their initial financing, or when the value of a property has otherwise fallen since the debt associated with a property was originated. The report estimated the debt funding gap at just under $73 billion.

“It is likely that some office projects will be prioritized for refinancing, but this will depend on a range of factors, including property types, specific assets, and existing relationships,” said Mellott. “Ultimately, this is a time where markets, assets, and relationships will play a critical role in determining the outcome for the office sector.

“Borrowers facing a potential refinancing gap may pursue additional equity or mezzanine financing to pay off the existing loan,” CBRE said in its report. “In addition, they may negotiate a discounted payoff with the lender, or an extension of the loan term if property income conditions are likely to improve. Ultimately, some borrowers may be forced to default.”

Debt funding gaps were prevalent across all major commercial real estate sectors during the global financial crisis of the late aughts, CBRE noted. However, this time, the debt funding gap is not appearing in all sectors but is heavily concentrated in the office space.

Despite persistent liquidity challenges, some deals are getting done. “You might not get an A-plus lender, you might get a second-tier lender with a higher rate, which would be the best available rate in the market,” said Ivan Kustic, a vice president at MetroGroup Realty Finance. “It doesn’t mean the market is frozen. It’s just a little bit more challenging.” Being immersed in the market and leveraging relationships is key, Kustic noted, as is knowing which lenders are still active.

Lenders will usually lean away from foreclosing on assets if it can be avoided, something that may–within reason–provide an impetus for facilitating some sort of refinancing. “The borrower has to bring something to the table, either market expertise, market management, (a willingness) to bring more cash into it,” said Kustic. “If the client or the owner is willing to manage (the property) for free or willing to contribute something, then we’ve seen lenders be way more patient and way more cooperative.”

The office sector’s challenges, meanwhile, extend beyond traditional office. “There is a tendency to paint all office properties with the same brush, regardless of whether they may belong to a more viable subsector,” said Kustic, offering medical offices as an example.

Recent refinancing exceptions may prove rule

Of the deals executed in recent months, many fell far below the $100 million mark. These included Crestone Partners’ $66 million refinancing of a 279,188-square-foot property comprising two interconnected Class A office buildings in Denver and Brause Realty’s $30 million refinancing of a 700,000-square foot Class A office property at 27-01 Queens Plaza North in the New York City borough of Queens. Allianz Global Investors originated the debt associated with the Denver Property, while Apple Bank provided financing for the Queens deal.

One deal, which exceeded $300 million, was executed by a pair of the commercial real estate sector’s most recognizable names. In June, a joint venture of Tishman Speyer and Silverstein Properties closed on $330 million refinancing of the Salmon Tower Building, a 32-story, 960,000-square-foot centrally located office tower at 11 W. 42nd St. in Midtown Manhattan. Newmark secured a five-year, fixed-rate loan for the joint venture, with Bank of America as the largest proportional lender and Taconic Capital providing mezzanine debt.

The duo of Tishman Speyer and Silverstein are hardly typical borrowers, however, nor is the property’s location. For other sponsors, netting similar debt may be as out of reach as the roof of the Salmon Tower.

A dearth of capital, but location is key

There is difficulty in obtaining debt for office assets generally, not just refinancings. “We’re seeing a lot of people shy away from construction risk regardless of the end-product,” said Margaret Grossman, managing partner and president at New York-based real estate investment, operations and development firm T30 Capital, suggesting that inflation and supply-chain issues are among the contributing factors.

“Downtown office properties in large urban areas will suffer the biggest price declines and the most financial difficulty.” That urban punch will impact the biggest metros in the U.S., said Mark Zandi, chief economist at New York-based Moody’s Analytics.. “This most notably includes the big cities in the Northeast corridor, Chicago and on the West coast.” This promises falling prices, said Zandi, though the fallout will not be limited to the sector.

Once an office space disappears, it remains “unclear how the vacant office space can be repurposed,” said Zandi. There has been much attention paid to repackaging former office properties as housing, but office-to-residential projects come with their own hurdles, which include building configurations and high costs.

Nevertheless, there are conversion projects underway in many cities and states as governments take steps to offer incentives. However, while the prospect of a replacement for existing office space may provide some relief to industries like retail that might fear a chain-reaction from offices shuttering, it is little comfort to the office sector itself, nor to its lenders.

“We expect peak-to-trough price declines of at least 30 percent nationwide, which means in the big urban areas price declines could be double that,” Zandi noted. “With fewer workers returning to downtowns, the demand for retail space will also be depressed as there are few people shopping and going to restaurants. Retail property prices are expected to decline by more than 15 percent peak-to-trough nationwide.”

“The availability of credit to finance office properties is tight and will get tighter as property prices fall and defaults mount,” said Zandi.

Alternative lenders, as well as alternative lending methods, are becoming more common in the commercial real estate space as the lack of debt from traditional providers has opened the door to financing methods like short-term loans and senior stretch loans, as well as to new players. How alternative lending methods will impact office properties is, as of yet, unknown, but will undoubtedly depend on investors’ appetite for risk.

Post-COVID work landscape a major factor

Many workers never returned to their offices after the early 2020 switch to remote work, and many others have only returned part time. This has created a major disruption in the office sector not seen in other asset classes. “The fundamental problem is the fallout of remote work on the demand for office space,” said Zandi. “Remote work is here to stay and will become slowly, but steadily, more prevalent as technology improves and new businesses form and optimize around remote work.”

In a recent refinance scenario analysis, Fitch Ratings determined that office is hardly the sole sector to suffer from high refinance risk as a result of higher interest rates. Loans backed by retail, hotel and mixed-use properties all showed a higher refinancing risk than the office sector, with office loans the most likely of the four asset classes to be refinanced. However, these sectors face more long-term stability than the office sector, whose entire future has been thrown into doubt in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The shift to remote work has impacted residential trends as well, with fewer people needing to live in close proximity to pricey city centers and downtowns. Therefore, proximity to major transit hubs that serve commuters is an important amenity to have. For example, space near major Mid-Atlantic transport hubs like New York City’s Grand Central Terminal and Pennsylvania Station, Washington, D.C.’s Union Station or Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station is increasingly attractive.

“There is reasonably healthy leasing demand for office properties that are Class A and in close proximity to major transit hubs,” said Grossman. “Everything else is pretty bleak.”

Despite current trends, though, Mellott he expects “opportunistic capital to start looking more closely at the office sector over the next year or so.” But, he cautions, lenders will likely continue to “approach office deals with caution.”

“While the short-term outlook for office remains challenging, and it may take longer to stabilize and recover than other property types, particularly for lower-quality properties, there are indications that things are likely to begin stabilizing over the next year,” said Mellott.

Read the September 2023 issue of CPE.

[ad_2]

Source link